Slum and Rural Health Initiative

Infectious diseases

Non-communicable diseases

Digital Health and Entreprenuership

Sexual, Maternal and Child Health

We fight social injustice by creating access to quality healthcare information and services in the world's most underserved region in Africa

Our Core

Our Impact

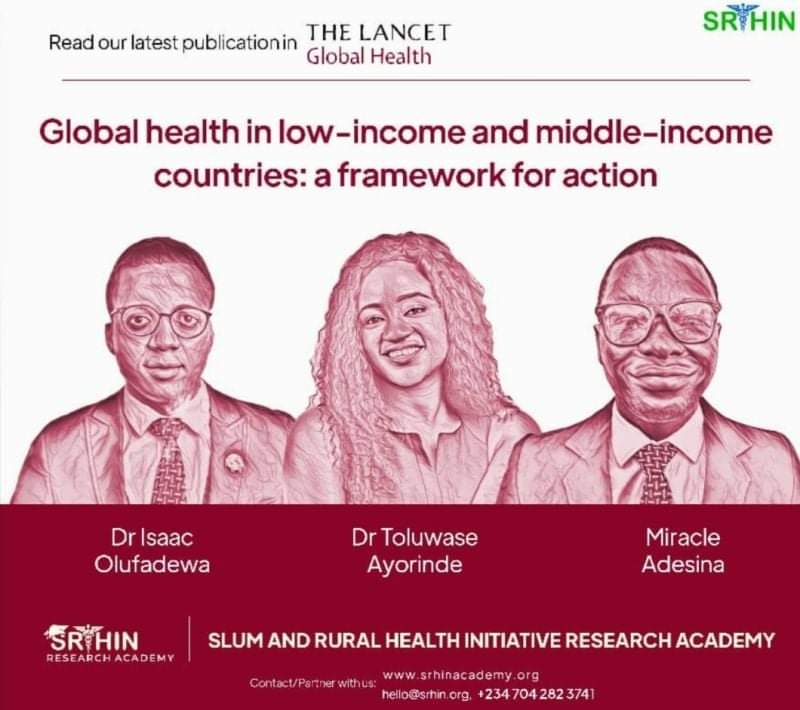

Members of our research academy have published in 200 peer-reviewed articles and presented in over 35 conferences across 5 countries.

About the Academy

Research Centers

AI for Low-Resource Public Health Application Center (ALPHA)

Center for One Health and Zoonotic Diseases(COHAZD)

Partnership for Reproductive Health, Infectious Diseasesand Maternal and Child Health Equity Center(PRIME)

Center for Excellence in Modelling Population Health and Enviroment Risks(CEMPHER)

Mental Health Innovation, Leadership and Entrepreneurship (MHILE) Centre